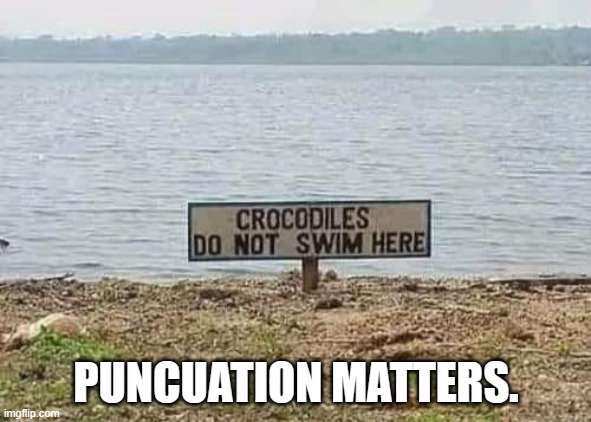

A short guide to the little writing rules we often second-guess

Let’s be honest, punctuation and capitalisation don’t usually get people excited. But if you’re writing anything that represents your brand, whether it’s a website, an Instagram caption or a printed menu, these little details actually matter a lot. They’re the invisible glue that holds your message together and makes it easy (and enjoyable) to read.

So let’s break down some of the most common trouble spots , especially for those of us working in branding, marketing, or design, and set the record straight using Australian English conventions and the Australian Style Manual.

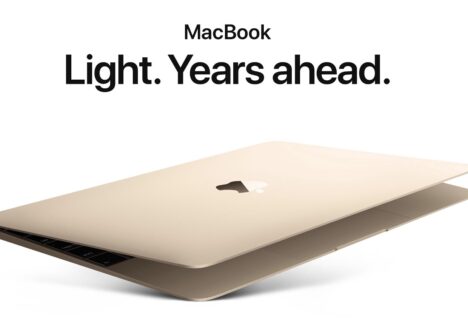

Logos are art, brand names are text

Here’s a big one: just because a brand’s logo is in all lowercase or all caps doesn’t mean that’s how the name should be written in a sentence.

For example, if you’re designing an email for a launch campaign, you’d write:

Correct: We’re thrilled to partner with Adidas on this release. Incorrect: We’re thrilled to partner with adidas on this release.

Adidas might use lowercase in its logo, but when writing the brand name in a sentence, it’s a proper noun, and proper nouns are capitalised.

Correct: We love brands like Zara, Burberry, Fendi, Chanel and Emporia Armani! Incorrect: We love brands like ZARA, BURBERRY, FENDI, CHANEL and EMPORIO ARMANI!

These brand logos may be styled in all caps, but that doesn’t mean we should write them that way in a sentence. It’s harder to read and looks like shouting!

Typography rules exist to keep writing legible, accessible and consistent. When we ignore them in favour of a logo style, things get messy (and hard to read). Unless a brand name’s styling is grammatically sound and widely accepted (like “eBay” or “iPhone”), stick with standard sentence capitalisation.

When you’re naming things in a sentence like products, apps, services, clarity is key.

- Avoid putting brand names in quotation marks, italics or bold.

- Capitalise proper nouns as you would any name.

- Use italics only if you’re introducing a new or unfamiliar term.

Example:

This feature is now available in Canva Pro and Adobe Illustrator.

Not:

This feature is now available in “Canva Pro” and Adobe Illustrator.

Sentence case vs title case: it’s a legibility issue

In Australia, sentence case is the recommended standard for headings and titles, meaning only the first word (and any proper nouns) are capitalised:

Correct: How to write product descriptions that convert Incorrect: How To Write Product Descriptions That Convert

The Australian Government Style Manual supports sentence case because it improves readability, especially on screens. And from experience, this isn’t just theory, I’ve personally found myself rereading headings, trying to figure out which words were actual nouns or just randomly capitalised. Sentence case removes that friction.

A perfect example of confusion caused by title case would be a sentence like:

“ATO Deputy Commissioner Will Day Highlights Our Newest Focus Areas To Help You Get It Right In 2025”

The constant capitalisation makes it harder to parse what’s happening and see what is a proper noun or not. With sentence case, the structure is far clearer:

“ATO Deputy Commissioner Will Day highlights our newest focus areas to help you get it right in 2025”

Title case may look more dramatic, but it slows readers down and increases the cognitive load. Especially in mobile or web environments, where users scan quickly, sentence case helps the brain process meaning without unnecessary pauses.

If you’re designing for a brand, it’s perfectly fine to use title case in a logo or aesthetic treatment, but for body text, headlines, buttons and web copy? Stick to sentence case.

Some punctuation reminders

Brackets

- If the content in brackets is part of the sentence, the full stop goes after.

- If it’s a standalone sentence, the full stop goes inside.

- If the bracketed sentence also ends the main sentence, the full stop still goes inside.

We always deliver on time (even when timelines shift). (This is especially helpful during peak periods.)

Quotation marks

- Use single quotation marks in Australian English.

- Use double quotes only when quoting within a quote.

Our client said, ‘We loved working with “the dream team”.’

Dashes

- Hyphen (-): joins compound words (custom-built). No space either side.

- En dash (–): indicates a range (20–30 mm). No space either side for ranges.

- Em dash (—): interrupts or adds emphasis—just like this. No spaces around em dashes in formal Australian English.

Some visual styles allow spaces around em dashes, but if you’re following the rules: no spaces is the standard.

Lists: keep the punctuation minimal

Lists should help people scan and understand information quickly—not work harder to decode formatting. The Australian Government Style Manual recommends:

For sentence fragments:

-

Use a lead-in sentence ending in a colon.

-

Start each point with a capital letter.

-

Do not use punctuation at the end of each bullet.

Correct:

Our services include:

Branding and strategy

Digital and print design

Packaging and product styling

For full sentences:

-

End each bullet with a full stop.

Correct:

Here’s what we did:

We designed the identity and packaging.

We developed the launch campaign.

We delivered press kits to media contacts.

Units of measurement: I don’t like it either, but there’s a space

If you’re writing quantities, whether on packaging, recipes, instructions or social posts, there are two key style rules to follow in Australian English:

1. Always include a space between the number and the unit

This is part of the SI (Système international) standard, which Australia follows. It improves readability and reduces visual clutter.

Correct: 250 g, 1.5 mL, 100 km/h, 20 s, 10 kJ

Incorrect: 250g, 1.5mL, 100km/h, 20s, 10kJ

This rule applies consistently across units: grams (g), kilograms (kg), litres (L), millilitres (mL), kilometres (km), joules (J), seconds (s), degrees Celsius (°C), and so on.

2. Unit symbols are lowercase, unless derived from a person’s name

This is where many people get it wrong. In SI units:

-

g for gram

-

m for metre

-

s for second

-

l would be correct for litre but…

There’s an exception for litre. Although “litre” doesn’t come from a person’s name (so technically “l” would be correct), many style guides including the Australian Government Style Manual recommend using a capital L to avoid confusion with the number 1.

So in practice:

Correct: 250 g, 2 L, 500 mL

Incorrect: 250 G, 2 l, 500 ml

Let’s wrap it up with a comparison:

Incorrect (cluttered and inconsistent):

JOIN US for our 2025 Launch Event with slack, Apple & nVIDIA — It’s going to be BIG! Get your samples (They’re Free!) at the Registration Table – and don’t forget: BRING ID.

Correct (clear, legible, and on-brand):

Join us for our 2025 launch event with Slack, Apple and Nvidia—it’s going to be big! Get your free samples at the registration table (and don’t forget to bring ID).

What changed?

-

Sentence case instead of scattered capitalisation

-

Brand names capitalised as proper nouns—not logo styles

-

Correct punctuation for brackets and dashes

-

Consistent tone and formatting

-

More readable, more accessible, more trustworthy

At the end of the day, punctuation, capitalisation, and formatting rules are about making your content clear, readable, and inclusive.

When you follow these standards:

-

People can scan your copy without guessing what’s a brand name, what’s a product, or what’s just poorly formatted.

-

Your content is easier to read for everyone, including people with cognitive processing differences, vision impairments, or screen readers.

-

You build trust. Because details signal professionalism, care, and consistency.

Especially in branding and marketing, where first impressions count and messages are skimmed more than they’re read, writing clearly isn’t optional, it’s part of the design.

If you care about great design, you already care about great writing. This is just the typography of language.